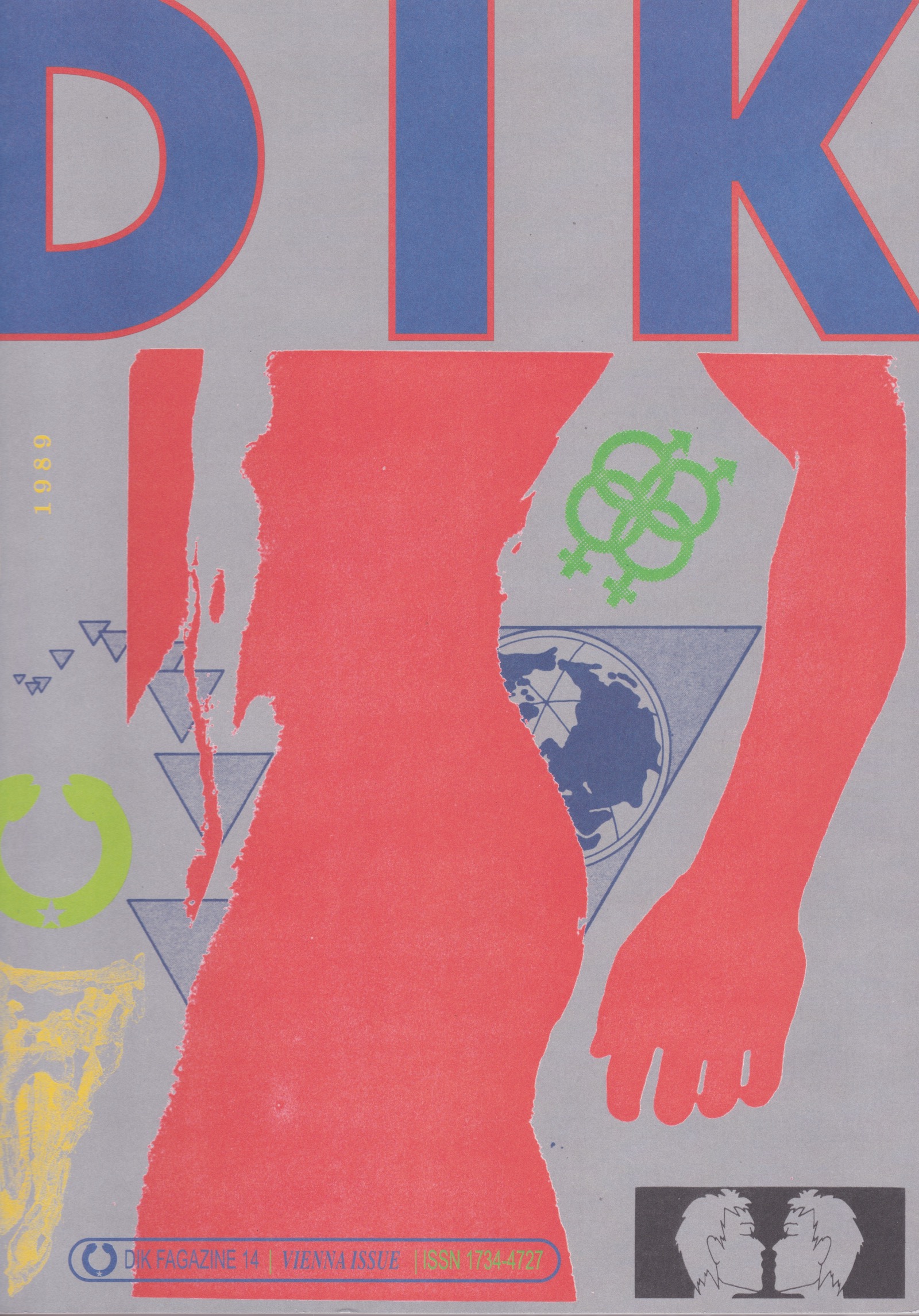

Interview im DIK Fagazine # 14

But Vienna was always ten years behind

“When I left Budapest, I had the first blood samples in the side box of my motorbike”:

Karol Radziszewski: When I started my research for this issue of DIK, I thought that everybody would be telling me about their crazy sex life and gay clubs, and how Vienna attracted queer people from Central and Eastern Europe. But Andrzej Selerowicz and John Clark told me the complete opposite. I was so disappointed. (laughing)

Kurt Krickler: Vienna was a very dull town, not only for the LGBTQ+ scene or community, but altogether. It was really right at the Iron Curtain, there was nothing, there was no hinterland. After the fall of the monarchy, Vienna had declined in the number of inhabitants, it was down to one and a half million. Today, it has two million inhabitants, and back then, during the time of the monarchy, it had two million. It was really not very interesting. It was gray and conservative and ugly, and can’t be compared with the Vienna we know today. A lot of movements started to emerge in the late 70s and early 1980s though: the women’s movement, democratic psychiatry, political movements, and the start of the LGBTQ+ movement, which was still ten years later than in France, for instance, or Germany, and certainly much later than in Scandinavia. But there was at least something.

In other countries, like in Germany and France, a new, more radical movement had already developed – one that wanted to go public and was not restricted to these discrete societies of friends that existed before, in the 1950s and 1960s. This was in the early 70s in Western Europe, but Vienna was always ten years behind. This was also due to the legal situation. The total ban of homosexuality still existed until 1971, ten years later than in Czechoslovakia and Hungary; in Poland, it had never even existed.

KR: In Poland homosexual acts were decriminalized in 1932, and it remained that way even during communist times. That was a unique situation in the context of the whole Eastern Bloc or even Europe.

KK: In Austria, the price for repealing the complete ban was that other anti-gay legislation was introduced: male to male prostitution was illegal, there was a ban on information and a ban on association if they caused public scandal. HOSI [Homosexuelle Initiative] Wien could only be founded in 1980, because we didn’t cause any public scandal in the first place. But it felt like the sword of Damocles hovering above our heads all the time. There was also a higher age of consent for gay men, which was 18 – compared to 14 for heterosexuals and lesbians. This law provision was actually in place until 2002. Vienna was definitely not a mecca or dream country for homosexuals. I think for Eastern Europeans, in terms of the LGBTQ+ scene, they would have probably rather preferred to go to San Francisco or London, or any German city, or Amsterdam. I don’t know which one would have been the preferred destination. But, in terms of the free world, Vienna happened to be the closest. So if people emigrated, Vienna was basically on their way, of course.

KR: Andrzej said that it was also the only option people had to travel without visa.

KK: Yes, at least for people from Poland and Hungary, but not for Czechoslovakians or Romanians. But, regardless of Austria’s visa policy, East Bloc citizens needed exit visas or permits from their authorities to be able to travel to Western countries. I remember when I went to Poland or to Hungary the first times, I didn’t need a visa. But to go to Czechoslovakia or GDR I needed one. But for the other places maybe not. Romania, I’m not sure anymore. And Yugoslavia, of course not. And when HOSI Wien started the EEIP [Eastern European Information Pool], it was clear that it was due to this geographic proximity. But we could not really present Austria as an example or role model for LGBTQ+ rights. On the contrary, we were actually worse off than most of Central and Eastern European countries.

KR: How did you come up with the idea of supporting or starting to organize something in Central and Eastern Europe?

KK: It was the then president of HOSI Wien, Wolfgang Förster, who put it out in an ILGA [International Lesbian Gays Association] Conference in Turin in 1981 – without knowing who was going to do the work and what work exactly. We wanted to operate internationally, and this was something Vienna was predestined for. But when we proposed it to ILGA, we had no clue who would do it and how. A few months later, John and Andrzej knocked at our door and said: “Hey, we’re here, we are a couple and we are getting bored. We want to do something! What can we do?” This was one of those decisive moments when things just happened, one of those few moments in the forty years of the history of HOSI Wien when I was active in it: the right people came together at the right time in the right place.

And then we started off, though Andrzej was the driving force of course. We really did it without any resources except personal ones, for instance, the time and energy that John and mostly Andrzej dedicated, as he did all the traveling. HOSI Wien was also crucial in creating an AIDS service organization of our own in 1985, the Österreichische AIDS-Hilfe in Vienna. I started working there in a paid job, and I used that to continue this EEIP work, but soon with a focus on AIDS work. One of the things we wanted to do was to share information. We could not give money, but we could provide magazines, video films, information, and free condoms, for example. It was very basic. When I worked with AIDS-Hilfe, it was easier to get all these materials. We just took them from the supply we had. It was subsidized, so producing forty video cassettes for distribution or getting free condoms was not a big deal. And all the scientific information from international medical journals which we copied for the staff in ÖAH’s seven regional centers was also copied and sent to Budapest, to Prague, and other places. The fact that researchers and doctors at the László Hospital in Budapest or the Institute of Sexology at the Prague Charles University were actually doing HIV counseling was of great help. Providing them with these scientific medical articles from those specialist journals was an important support. We did this on a regular basis for years.

KR: This was already in the mid-1980s, right?

KK: Yes, it started in 1985 – so still before the fall of the Iron Curtain which was four years later. We had a lot of contacts, and the AIDS-Hilfe regularly received visitors from Hungary, from Czechoslovakia, from Poland, from Russia, who came to see what we were doing. For Hungary and Czechoslovakia, it was actually a model. AIDS-Hilfe had counseling centers where gay men were working in central positions, and were also controlling and influencing the public health approach, and the politics behind AIDS work.

KR: You mentioned cassettes. Were you copying videos that already existed, or were you recording your own?

KK: It was existing material. We didn’t produce any new films.

KR: Was it material from the US or more local productions?

KK: All kinds of videos. German TV documentaries that we recorded and then circulated as copies. There were also short clips or spots that were shown on television for prevention purposes, just thirty seconds or one minute. Those were the kind of things we copied. People who were doing HIV/AIDS work in Hungary, for example in the László Hospital, came to Vienna. I also visited them once. Even the Hungarian television came to Vienna, making a TV reportage about the response to AIDS in Austria, which was broadcast in September 1985. I remember because the president of AIDS-Hilfe, Reinhardt Brandstätter, who was my partner at that time, was also interviewed on that occasion. He insisted how important it is that gay activists, gay people, are part of the response to AIDS, and that it’s important that gay organizations exist to reach out to gay men. I remember that much later somebody from Hungary told me that when he watched that interview, he laughed about this naïve guy from Vienna with his “utopian“ ideas. But two and a half years later, the idea materialized. In May 1988, the first Hungarian gay organization was founded. So actually, it was not as utopian as some people in Hungary thought it was.

We were realistic about the socialist regimes in Eastern Europe, but we were not so anti-communist that we would say it’s completely lost. It was an ambivalent situation, because we were all leftist of course, so we would neither go smash communism nor think it was great. We were realistic, and we could see what happened there. But being there also made us realize that things are not just black and white either. It’s not as if in Hungary everybody suffered in a concentration camp.

KR: You had this fantasy of communist countries realizing this utopia of the left?

KK: No, we were realistic. I don’t think we had this illusion. Our thinking or our consequence was not that the idea of socialism is bad as such, because this countries failed to implement it. But, of course, we knew the welfare states in Scandinavia are the most socialist in the end, because what the communist countries did was not socialism anyway. It wasn’t really a debate, because we had no time for those kind of meta level debates. (laughing) I think it was rather the political Marxist-Leninist groups that spent their time debating these things, but we were more practical people.

KR: Marx and Engels are holding hands on the cover of the book you published: Rosa Liebe unterm roten Stern. Zur Lage der Lesben und Schwulen in Osteuropa [Pink love under a red star. On the situation of lesbians and gays in Eastern Europe].

KK: That was a famous cartoon at that time, so we just stole it and used it for that purpose. Back then everybody stole things, nowadays you wouldn’t dare to do that because of copyrights. (laughing)

KR: Was AIDS-Hilfe an LGBT organization or was it dedicated to HIV/AIDS in general?

KK: It was a general one, but it was gay-dominated. It had three roots: it started off as a joint venture, which was unheard of at that time, in the mid-80s, between HOSI Wien, which already existed, the gay and lesbian organization, and civil servants from the Federal Health Ministry. There was a very committed doctor, Judith Hutterer, who actually treated the first HIV/AIDS patients in Vienna. She was really on the same wavelength as us, and she knew you can’t have hard measures, that would intimidate people and would make them panic. You really have to work with gays, and reach out to them on equal footing, on eye level. So the three came together but the ministry dropped out a few months later, once we got public funding, because it was their office in the ministry that would decide about the subsidy and the money. Of course, they could no longer be board members due to conflict of interests. But the founding history was really unheard of. That was a big success of the gay movement and also established it as an important player in Austrian politics, although it was still very difficult to get rid of the anti-gay laws. The biggest regret I have in this context is that HOSI Wien and the gay movement did so much for society, especially in the AIDS crisis, but we didn’t get anything back in return. In Scandinavia, it was clear that same-sex partnership would be legally recognized because people suffer when their partners die, and then they have no rights at all. Everywhere gays have done a great job, in Scandinavia, England and other places, in AIDS prevention work, reaching out to gay men, and that was recognized by society at large. In Austria, however, these merits were completely ignored in politics, there was no credit. That’s where I feel very frustrated and bitter about Austrian politics. There was no reward or acknowledgment of the great work we did in the AIDS crisis.

KR: You mentioned you shared your experience with neighboring countries?

KK: In June 1986, I was in Budapest meeting with some activists, which Andrzej had already known before. We were talking about how we could support them in AIDS prevention. In Vienna, we were already doing anonymous HIV testing. But you had to have a counseling talk with one of the doctors before you took the test so that you’d be informed what your options were if the test was positive or negative, and so on. You didn’t just give your blood and get the positive results per mail. There was nothing like this in Hungary. So we came up with the idea that, if they had the possibility to take care of taking blood in a similar counseling setting and bring the blood samples to Vienna, we could make the tests free and anonymous for them, too. And there was a person in the group who could do that: László Ramsauer, a medical doctor and psychologist. So he started to take blood samples. When I left Budapest back then, I already had the first blood samples in the side box of my motorbike. That was still in the communist era. But nobody asked me at the border. (laughing) And later, gay stewards at MALÉV, the national Hungarian airline, smuggled the samples to Vienna. It wasn’t huge quantities. They delivered it to ÖAH’s counseling center in Vienna, and then we tested it and returned the results. The doctor would then hand them out to the people in Budapest. But we only did this for a couple of months or maybe a year, because the same people then actually persuaded the Hungarian authorities to create their own AIDS-Hilfe in Budapest, they called it AIDS Segély – AIDS-Hilfe translated into Hungarian. It opened in October 1988 at Karolina Street. I know because I’ve just finished this section for my website (homopoliticus.at ). That was actually the Austrian model they took: don’t have it in a hospital, but in a neutral place where people can enter a building without anybody knowing that they were going to take an HIV test.

KR: So actually there was quite a lot of exchange in the 1980s.

KK: In the late 1980s, we had a lot of media coming to Vienna to see how we dealt with AIDS prevention work, from Croatia, from Poland, from Hungary. In 1989 we had the ILGA world conference in Vienna, and I remember that Henning Mikkelsen from the WHO, the World Health Organization, was here to talk to the participants. Of course, some people from Eastern Europe were there already. And from that moment on, he actually very much supported the Eastern European conferences of ILGA. There had already been these ILGA subregional conferences for Eastern and South Eastern Europe since 1987 which HOSI Wien/EEIP helped co-organize. The first took place in Budapest, and then in 1988 in Warsaw, and in 1989 in Budapest again. Henning basically got introduced to all the activists in the region, and from then on he provided substantial funding from WHO’s AIDS program to help finance travel and participation costs for the participants from Eastern Europe. Western Europeans attended too. In 1990, this subregional ILGA conference took place in Leipzig, in 1991 in Bratislava, in 1992 it was in Prague, and in 1993 we organized it in Vienna. I remember how crucial the WHO funding was. We received 100,000 schillings (€ 7,270), so we could finance the participation of more than 200 people from Eastern Europe in the conference. After 1989, of course, the movement had developed extremely in the region. In 1994 the conference was held in Palanga, Lithuania, and in 1995 it took place in Kyiv – that, however, was a disaster, and it hardly took place.

KR: Yeah, Andrzej mentioned that it was a mess…

KK: And in 1996 the last of these conferences took place in Ljubljana. After that, there was obviously no need for these subregional conferences any more. People from that region could now participate on equal footing in the ILGA World and European conferences. They were free to communicate and travel as they wished. For the same reason, HOSI Wien had already officially closed its Eastern Europe Information Pool in 1990.

KR: You were not traveling as much as Andrzej?

KK: No, in the 1980s it was not so often actually. I had been to Budapest a few times, four times in Prague because they also created an AIDS-Hilfe organization there, and as mentioned, I attended the EEIP conferences, where I worked, together with Henning Mikkelsen, on the AIDS input and the funding. In 1986, I was in Warsaw to meet with activists, together with Andrzej. I was also in Bucharest in 1992. Together with John, Henning and others to meet both activists and officials in the ministries. But that was already as a representative of EuroCASO, the European Council of AIDS Service Organizations. And Ljubljana of course! For example, we were a whole delegation from Vienna to attend the 2nd Magnus Festival in 1985. It was quite impressive, because you couldn’t see a difference. It was the same open-minded bubble like we had in Vienna in the alternative scene, that hadn’t yet touched the mainstream.

KR: Yes, Slovenia was very progressive. The Ljubljana LGBT Film Festival that started in 1984 is the oldest film festival of its sort in Europe.

KK: Yeah, they also had an exhibition there. It was great. We also had a workshop where we introduced the Austrian movement and presented the work of HOSI Wien and Rosa Lila Villa. And Gudrun Hauer gave a lecture on the persecution of homosexuals during the National Socialist era.

But in general, I was rather part of the team that would put together information, with John translating it into English, for the annual EEIP report we published on behalf of ILGA. And also for LAMBDA-Nachrichten.

KR: This was HOSI Wien’s magazine, right?

KK: Yes, by now LAMBDA–Nachrichten is the longest published gay magazine in the German-speaking region. It has been there for more than forty years, since 1979. I was part of it for 39 years, from the beginning until 2018. And for 20 years I was even the editor-in-chief. It was a very important source of information. Andrzej did a lot of writing and reporting for the international section, and many activists from the region contributed articles, f. ex. about the GDR, such as Ursula Sillge and Eduard Stapel. We gave them the space to express themselves. At that time, there were a lot of gay magazines around Europe. And our articles were translated and republished in Norwegian, Dutch, French, and Italian gay magazines, all over, because it was information hardly anybody had, unless they traveled themselves or interviewed people.

KR: Andrzej was laughing because one of the Polish guys who was always a troublemaker was apparently complaining that it is this imperial Austrian approach that Vienna is, again, the center for the beginning of all this Eastern European movement. (laughing)

KK: I think we tried not to be paternalistic. If we were Dutch we could have said, “look, this is how you do it. This is an LGBTQ+ paradise, we know how to do things.” But in Austria, in Vienna, we could not tell anyone that we were the mecca for whatever. No way. We couldn’t make presents, we couldn’t give out money. We were just facilitating exchange with our very limited resources.

KR: Okay, so last question: is Vienna East or West?

KK: (laughing) I think geographically speaking it’s East. That’s easy. Prague, Berlin and Ljubljana are much more West. And in terms of community building, LGBTQ+ scene, acceptance in society … I think it was also East. And also in terms of modernity and progressivity, it was very backwards. Austria is, after all, a catholic country. You can’t imagine how gray and ugly Vienna was back then, forty years ago.